About four months ago, I had a breakdown at work and was sent home. I work for a Division I athletics program, and part of my job is to run summer bridge programs for incoming student athletes. These programs are intended to help bridge the gap between high school and college. They are intense, 24/7 operations, and immediately after the last one finished, I had to begin prepping for fall term. And somewhere in that transition, I just shut down.

I went into my director’s office and told her I couldn’t do this anymore. I just couldn’t. I’ve always been the guy in the office who says yes to everything. I’d always assumed that the solution to any problem was to simply work harder. In the past, this had paid off. But in that moment, I realized I’d blown through some emotional gate inside myself that I didn’t know about.

My director, a very thoughtful woman, told me to go home. She didn’t say it like I was going to get fired. It was obviously out of compassion that she sent me away.

My wife came home to find me in bed, curled up on one side. We have three children, and I am the primary provider. Mel works part-time at our kids’ school, while I work full-time at the university and make additional income writing. I’m not going to say that my life is more stressful than Mel’s, because it isn’t apples to apples. I think mothers are the hardest working people in the history of ever. Every day, I am blown away by what Mel accomplishes during the day, and any time I can give her a break, I do.

But what I would like to point out is that when Mel came into our room, I nearly cried. I highlight this because I’m not the kind of person to cry. In fact, when my father died, I didn’t cry. It’s not that I wasn’t sad; I just couldn’t find the tears. What I felt when Mel came in was the rich sense of failure. I felt anxious and depressed because I knew that she was counting on me. I knew that the children were counting on me. I felt a paternal obligation to provide that had been drilled into my head as a boy who would one day be a father. I felt pinched between a rock and a hard place because I knew I needed to pick myself up and keep going into work, but I honestly didn’t know where I’d find the strength to do it.

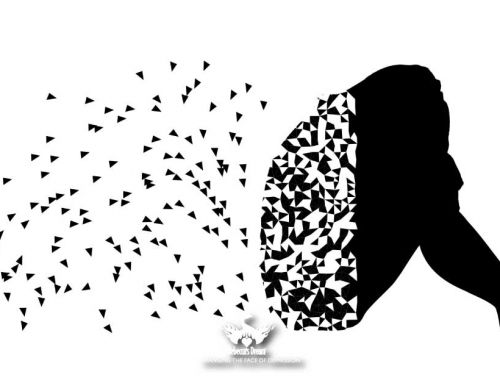

The stress of being a full-time-plus working father had somehow caught up with me, and the thought of going into work the next day felt like walking into a burning room, but the thought of letting down the people whom I loved the most in my life, my wife and three children, felt like rich, pungent failure, and in between was me, curled up on a bed, feeling like the only option was suicide.

Mel asked me what was wrong. She asked me if I’d lost my job. “No,” I said. “It’s more complicated than that.”

Then I asked her if she’d hold me. She crawled in next to me, and we just stayed like that for a while as I collected my thoughts.

Eventually, I told her what had happened at work — about the stress I was feeling and the expectations I just wasn’t sure I could meet — and as I spoke, I felt so weak. I felt pathetic. I wanted to know why I wasn’t strong enough. I was a man. I was a father. I should be capable of handling work and family. But in that moment, I didn’t know if I could.

We discussed backup plans if I did end up losing my job. I made an appointment with a therapist, which ultimately resulted in repeated visits and lifestyle changes.

What I didn’t know until recently is that 30.6% of men have suffered from a period of depression in their lifetime, and the suicide rate among American men is about four times higher than among women, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Women are more likely to attempt suicide, but men are more likely to succeed.

As a man, I can say, honestly, that the hardest part about living with depression and anxiety is admitting to it. It’s so difficult to acknowledge the symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression, and how all of these symptoms can be exacerbated through work and family stress. Because the reality is, as much as I love my wife and children, fatherhood and marriage have been the hardest challenges of my life. Not that I can’t do it, because I can. But there are going to be moments that are more stressful than others, and without proper help, those moments can push a loving, dedicated father over the edge.

So much of this comes from the stigma associated with mental illness. Pair that with the societal pressure to “man up,” and it further stigmatizes someone who is already hurting. Normalizing mental health is a priority for society as a whole, of course, but we also need to ensure that fathers feel comfortable sharing their struggles and showing their emotions. We are not there yet, because if we were, I’d have probably felt far more comfortable reaching out to my wife, my supervisor, and anyone else who could help long before I reached my breaking point.

Source > ScaryMommy.com

Image > istockphoto