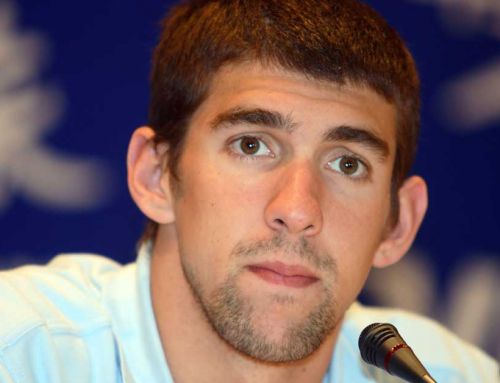

Michael Phelps locked himself in his bedroom for four days three years ago. He’d been arrested a second time for DUI. He was despondent and adrift. He thought about suicide.

“I didn’t want to be alive,” he tells USA TODAY Sports. “I didn’t want to see anyone else. I didn’t want to see another day.”

Family and friends — “a life-saving support group,” Phelps calls them — urged him to seek professional help. He got it. And now he wants others who are suffering from mental health issues to find the help they need.

Some will scoff at this. Phelps is the golden boy of the Olympic Games. Fame and fortune are his. Really, what could be so bad in his life?

That is never the right question. People from all walks of life suffer from a range of mental illnesses. Roughly 44 million Americans experienced some form of mental illness in 2015 (the most recent year for which numbers are available), according to estimates by the National Institute of Mental Health. That’s nearly one in five people aged 18 or over.

Athletes may be at increased risk, according to research by Lynette Hughes and Gerard Leavey of the Northern Ireland Association of Mental Health, who found that factors such as injuries, competitive failure and overtraining can lead to psychological distress. An NCAA survey of athletes found over the course of a year that 30% reported feeling depressed while half said they experienced high levels of anxiety.

Brent Walker, associate athletic director for championship performance at Columbia University, says he didn’t want to deal with the mental health side of performance when he began working in the field. Now, he says, “it is difficult to separate the mental health piece from the performance side of it.”

NBA legend Jerry West has struggled for decades with dark bouts of depression and low self-esteem. Sometimes people tell him he’s brave for speaking openly about it. He says that’s not courageous so much as honest.

“Some people hide their pain,” West says. “I’m not proud of the fact that I don’t feel good about myself a lot of the time, but it’s nothing I’m ashamed of.”

Wilbert Leonard, a sociology professor at Illinois State, says he thinks consciousness in the broader world can be raised by prominent voices from the sports world — like Phelps, West and Marshall — and perhaps begin to chip away the societal stigma too often attached to mental illness.

“It’s John Wayne syndrome, that stiff upper lip — keeping your feelings to yourself and not letting anyone know you’re hurting,” Leonard says. “That plays out in the sports world and it plays out in the larger society.”

Athletes face pressure to perform, often in the face of intense public scrutiny, while competing in a culture that inhibits them from seeking the help they need.

“For the longest time, I thought asking for help was a sign of weakness because that’s kind of what society teaches us,” Phelps says. “That’s especially true from an athlete’s perspective. If we ask for help, then we’re not this big macho athlete that people can look up to. Well, you know what? If someone wants to call me weak for asking for help, that’s their problem. Because I’m saving my own life.”

Imani Boyette

Screaming in a soundproof room

The first time Imani Boyette tried to kill herself she was 10.

Boyette, 22, is a center for the WNBA’s Atlanta Dream. She suffers from clinically diagnosed severe depression that she attributes to a combination of circumstance (she was raped as a child by a family member) and happenstance (her biological makeup).

“You feel like because you’re not happy — when you should be happy — that you’re hurting people around you and a burden,” she says. “At a certain point, it just gets easier to shut up because people get sick of hearing you’re not OK when you’re not sick on the outside.”

Boyette says she tried to kill herself three times. “I wasn’t looking for help,” she says. “I wasn’t looking for resources. … I didn’t have anybody I could talk to, I could touch, who understands this hell I’m in.”

That’s why Boyette is telling her story. She wants to be the role model she wishes she’d had in her darkest hours, not that it’s easy to do.

Her brother, JaVale McGee, plays for the NBA champion Golden State Warriors and her husband, Paul Boyette Jr., is a defensive tackle for the Oakland Raiders. They met when both were athletes at the University of Texas. She told him then about her childhood abuse, by way of explanation of her night terrors.

“After I got married, I went into a deep depression, which makes no sense whatsoever,” she says. “It’s, like, the happiest time in your life. And it’s hard to convince your husband this is not because I don’t love you. I just can’t love you out of this depression, out of this fog.”

She describes the days when she can’t even get out of bed or brush her teeth. It’s as if she were in a straightjacket, she says, screaming in a soundproof room where no one can hear her, even her husband. Soon the screams are more like echoes and she envisions a glass wall where she presses her hand against his.

“I tell him just being there is enough,” she says, eyes moist. “You don’t have to understand or see my pain, but just acknowledge it. And be there.”

Mardy Fish

It’s OK not to be OK

Mardy Fish was ready to play Roger Federer in the fourth round of the 2012 U.S. Open when he mysteriously withdrew from one of the biggest matches of his life for “health reasons,” as his handlers said at the time. It was for severe anxiety disorder, which over time had led Fish to panic attacks, sleepless nights and days barricaded inside his home.

“It’s OK not to be OK,” he says. “To show weakness, we’re told in sports, is to deserve shame. But showing weakness, addressing your mental health, is strength.”

Sports is measured in the binary way of wins and losses; facing up to anxiety is more complicated than that. “There is no quick fix where all of a sudden you wake up and it’s gone,” Fish says. “There is no sports movie ending here. This is the reality of sports stars being real people.”

He says 2012 is when “it all came crashing down” and he could no longer find his “happy place.” His psychiatrist prescribed medication. That helped. He has since slowly begun to ween himself and set small goals. One was traveling alone for the first time in years.

Fish married Stacey Gardner, an attorney and model, in 2008. “I’m so glad my struggles happened when they happened,” Fish says. “I can’t imagine being single and young, going through this. My support system has been massive.”

Fish took off the 2014 Tour to have a catheter ablation operation to correct misfiring electric impulses in his heart, then made a brief return to competitive tennis in 2015. He has since become a serious golfer. He finished tied for second in the American Century Championship celebrity tournament recently, behind former pitcher Mark Mulder and ahead of NBA star Stephen Curry, who was fourth.

Isn’t golf stressful?

“The truth is you want stress in your life,” Fish says. “You don’t want an actual anxiety-free life. What would the fun be there?”

Rick Ankiel

Hardly immune to inner pain and torture

Rick Ankiel was on the mound for the St. Louis Cardinals against the Atlanta Braves in Game 1 of the 2000 National League Division Series when he found he couldn’t do what had always come so naturally. Ankiel, the pitcher, couldn’t pitch anymore.

He threw five wild pitches in an inning; no major leaguer had done that since 1890. More starts produced more wild pitches. He was never the same.

“For anyone who hasn’t had it happen to them, they don’t understand how deep and how dark it is,” he says. “It consumes you. It’s not just on the field. It never goes away. … It’s this ongoing battle with your own brain. You know what you want to do — in your heart. But your body and brain won’t let you do it.”

Ankiel would eventually have to give up his pitching career. Remarkably, he would come back years later as an outfielder. He is one of two players in major league history who have started a postseason game as a pitcher and hit a home run in the postseason as a position player. (The other? Some fellow by the name of Babe Ruth.)

Anxiety on the mound led to obsessive thoughts in his daily routine. TV analysts called him weak. They said he lacked mental toughness.

“I can’t imagine how bad it’d be with social media nowadays,” he says. “There’s such a stigma, especially with men, that you can’t falter, and that you shouldn’t get help.”

Ankiel found himself envious of players who had physical injuries that rehab could fix. He turned to therapy, breathing exercises and different medications — mostly to no avail.

Ankiel was USA TODAY Sports’ high school baseball player of the year in 1997. Some touted him as the second coming of Sandy Koufax. And then, poof, it was gone.

“It was beyond frightening and scary,” he says. “We’re getting paid millions, but that doesn’t mean we’re immune to inner pain and torture.”

Ankiel wrote about all of this in The Phenomenon: Pressure, the Yips and the Pitch that Changed My Life, which came out this year. It tells of how he tried vodka and marijuana to calm himself. Nothing worked. Enter Harvey Dorfman, the late sports psychologist, who became a father figure in Ankiel’s darkest hours and helped “save my life” as his pitching career unraveled. Dorfman, who wrote The Mental Game of Baseball, helped Ankiel face his abusive childhood.

“For athletes, you want to try to turn over every stone possible to be at the best of your ability,” Ankiel says. “So if there’s a doctor or counselor who can help you, why not turn over that stone? Having a culture conducive to mental health is big. I think we’re getting there. Just about every (MLB) team has a psychology department. I’m glad we’re starting to understand. We’re all human, and I think the more we talk about mental health, the better.”

Royce White

Bigger than diagnosis and labels

Royce White left the NBA three years ago amid demands for a better mental health initiative from the league. Today, playing basketball in Canada, he speaks bluntly about mental illness and salts his conversation with colorful metaphors and off-color language.

He grew up in Minneapolis, largely raised by a single mother and grandmother. Speaking his mind always came naturally.

“I didn’t have men around me growing up who saw having anxiety as weak or not tough enough,” White says. “I grew up with a lot of diversity. Instead of having that traditional one-male role model, I was allowed to have many. And maybe it’s just where I’m from, but that whole masculinity (stereotype) — men can’t show weakness (crap) — wasn’t around.”

One of White’s male role models was his fiery high school coach, Dave Thorson, now an assistant coach at Drake, who led White to therapy. An in-school family practitioner ultimately diagnosed him with generalized anxiety disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder. Since, he’s embraced his illnesses rather than hide them in silence.

White, the Houston Rockets’ first-round draft choice (16th pick overall) in 2012, says the headlines that surfaced in 2013 — referencing the panic attacks and anxiety he experiences on planes — were blown out of proportion and misleading because his overall message was calling for a more prudent mental health policy and better understanding. White flew 20 times at Iowa State and now flies with his team in Canada.

“It’s been painted as me wanting special treatment because of anxiety,” White says. “No, I’m saying I need the same type of support as anyone who is struggling. Call it whatever the hell you want to call it. There are specific injury doctors for players” with bum knees and sprained ankles.

White says when he requested an individual doctor, NBA officials then told him if they made an accommodation for him they’d have to do it for 450 players. He played in just three NBA games — zero points and seven personal fouls for the Sacramento Kings — as he bounced around the NBA and its developmental league for several seasons.

Last season White played for the London (Ont.) Lightning of the National Basketball League of Canada, where he is the reigning league MVP and the Lightning are the reigning champion. His last affiliation with the NBA was the Los Angeles Clippers’ summer league team in 2015.

“It’s not about me in the NBA,” White says. “You hear all the time about mental health stigma and people being ashamed. Well, there are people across the country who need help, say they need help, and aren’t getting it. We should be talking about them, too.

“Mental health is bigger than diagnosis and labels.”

Allison Schmitt

Therapy is the best tool

Swimmer Allison Schmitt executed a flip turn, as she’d done many thousands of times before, as she competed in an event in Austin, Texas, in 2015. And then, out of nowhere, midway through the 400-meter freestyle, she quit.

“That last 200 meters I was like, (expletive) this,” she says. “I knew I gave up, but I didn’t know why.”

Michael Phelps, her friend and frequent training partner — was at the meet. Months earlier, Phelps and Schmit sat in a burrito restaurant and discussed the suicide that week of actor Robin Williams. Schmitt had said she could understand why he did it. At that point, Schmitt says, “Michael knew something was up.”

Schmitt had contemplated suicide herself. She’d thought about driving off the road on a snowy night to make it appear as accident.

Phelps approached her on the pool deck after she quit on that 400 free. Bob Bowman, who coached them both, also arrived. And Schmitt’s pain soon came pouring out — the tears, the sadness, the emptiness. Schmitt says she began seeing a psychologist soon after. Therapy, she says, “makes training for the Olympics seem easy.”

She found it difficult to be vulnerable and talk about her weaknesses. She’d been taught all her life to rush through, persevere and come out stronger. She felt embarrassed and ashamed.

“But now, therapy is the best tool I’ve encountered in this life,” Schmitt says. “For a lot of athletes, their arena is their sanctuary. But for a lot of struggling people in society, the therapy room is a place of peace they can’t find anywhere else.”

Not long after her tearful epiphany on the pool deck, Schmitt found out her 17-year-old cousin in Pennsylvania had committed suicide. Schmitt says this promising basketball player “had it all going for her. She was the life of the party, always making people laugh.” Schmitt pauses. “But, no one knew how dark of a place she was in.”

This, Schmitt says, is why she is pursuing her master’s degree at Arizona State to become a licensed clinical social worker and counselor. (She earned her undergraduate degree at the University of Georgia in psychology.) She realized after her cousin’s suicide that mental health struggles should not be hidden.

“Depression is something that’s in you,” she says. “It’s not wanting to get out of bed, continuously feeling sad and down on yourself. It’s not wanting to exist, sometimes. There’s no on-and-off light switch. When I hear coaches, athletes telling people to ‘snap’ out of it, it makes me mad. Because you could be pushing them down that dark hole further.”

Brandon Marshall

My purpose on this planet

Brandon Marshall remembers a group therapy session when he noticed the scars on the wrists of the woman sitting next to him.

“I realized that someone needs to stand up for these people. This has become my purpose on this planet. Football is just my platform.”

This was during Marshall’s three-month stay in 2011 at McLean Hospital, a psychiatric hospital and affiliate of Harvard Medical School, where he was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. That was the first time he had a name for the illness that had led him to run-ins with the law and light-switch behavior he never understood. He says his diagnosis had a salutary effect on his family, including his mother, Diane Bolden. Marshall says she was able to confront her own depression and is now five years sober.

“I made everyone around me healthy,” he says.

Marshall and his wife Michi founded Project 375, an organization dedicated to eradicating the stigma surrounding mental health by raising awareness.

“Where we are now with mental health is where cancer and HIV were 20 years ago,” Marshall says. “It’s extremely important for us to have this conversation not just in sports, but in society. It’s important for us to change the narrative.

“There are over 100 million people living with some type of mental illness and those people then touch so many people in their lives.”

“It’s a lot of preventative work,” he says. “I know when my most stressful times are, and so I plan for it. During the season, it’s very stressful. So I have to be proactive. BPD can be different from one person to the next. For me, I don’t use medication. I consult my doctor on FaceTime or Skype when needed. I meditate. I use my Christian faith to hold me accountable.”

NFL players are seen as gladiators who can fight through anything, Marshall says.

“Well, we can do that — by being honest and vulnerable,” he says. “This is America’s sport, so whenever we’re able to take our masks off — to 90 million people, avid football fans — it provides the ability to move culture.”

Jerry West

The dark place that doesn’t go away

Jerry West is Mr. Clutch. He’s The Logo. He’s a master architect, building teams behind the scenes.

He’s also, at 79, a lifelong sufferer of depression. Or, as he calls it, the dark place.

“This is something that doesn’t go away, this depression,” West says. “When I go through it, it’s almost always based on my (low) self-worth and self-esteem.”

West sees his suffering less as an illness and more as a product of a tormented childhood of abuse at the hands of his father. That’s part of why West turned to basketball as a scrawny kid — a “misfit with no confidence,” in his words — in West Virginia. It was a safe haven where he could build confidence.

“Everyone is driven by different things in life,” West says. “To some degree, based on some of the things I saw growing up, I was looking for an escape. I was just looking for something that I’d be appreciated for. I guess I was looking for a sanctuary.”

Sometimes he played all by himself in a fantasy world where he always splashed a game-winning buzzer-beater. “For anyone who saw me,” he says, “they probably said, ‘My God, this kid is crazy.’ ”

He emerged from childhood sanctuary to be one of the greatest players in history. The darkness never left him, though. “I feel that same sadness at times now,” he says.

He took his West Virginia Mountaineers to the championship game of the NCAA tournament, where they lost. His Los Angeles Lakers made the NBA Finals nine times — and lost eight.

Team camaraderie buoyed him during his playing days. As a team executive — with the Lakers, Memphis Grizzlies, Golden State Warriors and, newly, the Los Angeles Clippers — he’s often alone in his day-to-day operations. “You’re the judge, jury and executioner,” he says.

The kid who wanted to be a hero, sinking all those game-winners in imaginary games, says he never wanted credit for his successes as an executive, though he helped to build dynasties with the Lakers and the Warriors.

“You’ll never see me on a (championship) podium or in a picture,” West notes. “It was never about me. Yet, on the other hand, there are times when I’d be down and out and you feel like you’d want someone to come up and say, ‘Hey, you’re pretty good at what you’re doing.’ That’s when the (depression) kicks in.”

West says he thinks he’s able to see talent and character through a different lens than other executives.

“Some of these kids, these players, they’re survivors,” he says. “In many cases I thought I was a survivor. That’s who I’m attracted to. Someone who’s been through something. And I always want to know, who was the person who made you feel? Or when was the moment when you felt like you belonged? Instead of going inward.”

Freud theorized that pain turned inward becomes depression. “It’s got to go somewhere,” West says.

For a long time, he had no idea why he felt the way he felt.

“I thought this was how all people felt,” he says. “I’ve always been different. But I like to think I’m different in a good way.”

Michael Phelps

All that glitters isn’t gold

For most of his solid-gold life, Michael Phelps saw himself in much the same way as the outside world did.

Phelps is 32 now and he wants the world to see him as husband, father and, yes, history’s most decorated Olympian — but also as a depression sufferer.

“It’s good for athletes to be open about who they are and for people to see we’re far from perfect,” Phelps says. “We’re not gods. I’m human like everybody else.”

When Phelps opened up about his difficulties he found he could help others while helping himself.

“Once I started talking about my struggles outside the pool, the healthier I felt,” he says. “Now I have kids and adults come up to me and say they were able to open up because I was open about my life.”

Phelps retired after the 2012 Summer Games in London — or so he said — but ended up coming back for a last hurrah in Rio in 2016, this time with his infant son Boomer and newlywed wife Nicole to cheer him on. Now he swears he’s really retired. And he doesn’t have to worry about what’s next; his calling as an advocate for mental health found him.

That story of mental anguish includes ongoing “depression spells.” He remembers they’d often come after his Olympic highs. All that glitters isn’t gold.

“You’re at the highest level of sport you can possibly get,” he says. “Then you’ll want to do something new, something crazy. That high to low can put you in a dark spot.”

Sometimes that darkness was consuming.

“Isolation can be crippling,” Phelps says. “When I’d see my therapist, I remember beforehand how much I hated going. Then every time after I’d walk out the door, I felt like a million bucks.”

Now he says he has the tools to get through the dark times and “I’m able to be a better husband, a better father, a better son, a better friend.”

Source > USA Today

Image > Rob Shumacher, USA Today